Marine litter in the oceans can’t be solved by volunteering. Project IKKAKU’s Vision for an Economic System That Combats Marine Pollution

Project IKKAKU is working to create an economic system that combats marine pollution. We spoke with Yuko Ueno, a representative from Leave a Nest America, about their plans.

The Japanese archipelago is no stranger to marine pollution, with so much waste washing up on Japanese shores every year. Marine pollution can refer to a variety of different kinds and amounts of waste. Yuko Ueno is the team leader for the Leave a Nest development department at Leave a Nest America, an organization that seeks to combat marine pollution by creating a new economic system through Project IKKAKU. She started at the company in its early stages, after having seen marine pollution first-hand whilst living on Okushiri Island off the shores of Hokkaido. We spoke with Ms. Ueno about different types of observation technology they are using for this project, which includes drones and satellite data, and what their plans are to create a movement to gain attention on this project.

Yuko Ueno

(Doctorate in Science) / Business Development Department / Employee of Leave a Nest, USA / During her years as a student, she studied microorganisms that inhabit extreme environments, aiming to bring light to the origin of life. She works on discovering projects which find their origin in universities, both domestic and overseas, and helping them gain traction as start-ups.

―How did Project IKKAKU begin?

Ueno: It started as a part of the “CHANGE FOR THE BLUE” project run by the Nippon Foundation which worked to fight marine pollution.

Sorabatake Memo

“CHANGE FOR THE BLUE” is an effort to eliminate marine pollution with stakeholders in the public, private, and academic sectors in order to create a societal movement to combat the threat.

https://uminohi.jp/umigomi/index.html

Ueno:This project was a collaboration between local governments and companies such as Coca-Cola Japan and Seven-Eleven Japan. Leave a Nest, on the other hand, teamed up with the Nippon Foundation and JASTO to start Project IKKAKU in 2019 to add a new dimension to this movement by using a start-up company to in order to turn cleaning up the ocean into a business.

―Most people view combating marine pollution as a form of non-profit activity. How does this play into boosting the economy?

Styrofoam and other plastics make up a large portion of sea pollution. As a part of Leave a Nest’s effort to educate children, we surveyed over 1,000 children. We found that most children thought that plastic was evil and people shouldn’t be using it. We believe, though, that depending on how we use it, plastic is one of our important resources.

The so-called “evil” part of it stems from not effectively controlling disposal methods. Using volunteers to pick up marine litter is what has been done up until now, but since people have to spend their own time and money to do this, these kinds of activities tend not to last long enough to have a real effect. There are also companies that make it a part of their corporate social responsibility program, but such programs usually shift their focus to large-scale natural disasters when they happen, so these can’t rely on either.

We found that if we are really going to have an impact on marine waste, we’re going to need to use research and development to find a way we can turn it into a business. So we tried to make a business where the more marine litter we collect, the more money we stand to make. We wanted to change the economic stance from a linear one, one where we create products, use them, and eventually dispose of them, to a circular economy, where the products are reused instead of being disposed of. We got a team together and set a limit of three years for ourselves to conduct research and develop a business model in which we could turn collecting marine litter into a business.

Team Building via Matchmaking between two Completely different fields; Leave a Nest's method for solving social problems Leave a Nest's Method for Solving Society's Problems

―How did you find talent that could be used to monetize the elimination of marine pollution?

Ueno:It’s important to understand that there are many different kinds of marine pollution. Marine pollution can range from the fundamental perception of how we use our natural resources, to the prevention of getting trash into the sea from rivers or figuring out a way to recycle and use the trash, so there isn’t a clear-cut problem we are faced with. It was important that we took a closer look at the problem to figure out what we could tackle. There isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution we can create that will solve all the problems, so we needed to create an organization of people from different backgrounds.

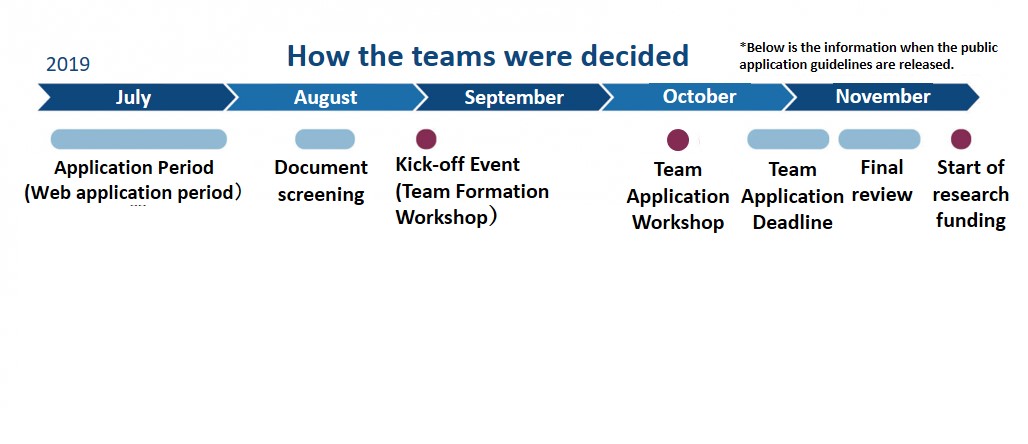

So we came up with bringing people from entirely different fields together to create unique teams and started recruiting members in July 2019. We mainly sought to recruit people who were interested in solving the world’s marine pollution problem. We created three different recruitment themes, “Science & Technology” “Business Ideas” and “Creative & Craft”. We had an idea of what kind of team we wanted to build, so we reached out to different members of Leave a Nest’s network when we started recruiting. We ended up getting some unexpected entries as well, for a total of 62 members.

―What was Leave a Nest’s method to figure out who went on which team?

Ueno:We held a two-day workshop to figure out how we would build the teams. We had each of the 62 members present their technologies and achievements in a ninety-second pitch.

We had each of the members watch each other’s pitches to figure out the teams amongst themselves and ended up with eight teams in total.

Members then volunteered to become team leaders, our only requirement was that they were from a start-up company. This is because start-ups tend to be more flexible in terms of management, as well as having more recent experience in presenting their ideas and concepts. We also wanted the team leaders to encompass Leave a Nest’s main vision.

Each of the eight teams set up a business plan then set up three year plans with a goal for each year. Each of the teams presented their goals and how they would achieve them using what each member brought to the table. Of the original eight teams, we ended up choosing to work with three of them: the Sea Pollution Monitoring Team, the Plastic Recycling Team, and the Marine Pollution Collection Team. They received a maximum subsidy of 150 million yen to fund their efforts.

―What did you look at when you were trying to figure out which teams would receive funding?

Ueno:The two main things we were looking out for were how diverse the teams were and how possible it would be for them to achieve their goal. The main premise of the project is to have their proposals turn into businesses within three years, so it couldn’t be too focused on vision visionary, or something that required too much research. The members would have to finish their research and development using what they already have in the first year, prove that it could become a business within the second year, and actually start their service by the end of the third year. We had researchers, particularly those from universities, join in on our effort, to help customize their technologies in order to meet the first year’s goal and to continue research and development whilst their business teams continued with the next phase.

Like I was saying before, sea pollution can mean a variety of different things. It’s important to be able to explain what the problem is, and how we can provide solutions for it. The teams that were chosen did a good job in laying these two things out for us. For example, the team that suggested we use satellites and drones to monitor marine pollution narrowed down their scope to coastal pollution in specific locations (Nagasaki and Shimane in this case). Teams that did this had a better chance of being chosen for funding. Technology seeds are not the starting point, and can easily be modified later if they aren’t sufficient. Having finished our first year proving concepts in 2020, we are using 2021 to figure out whether or not monetization is possible, and will bring it to the market by 2022.

―What kind of members make up the three chosen teams?

Ueno:The “Debris Watcher” is working on the creation of a satellite and drone-based sea waste detection system.

Ueno:This team uses satellites to collect data over a wide region, then drones to get a closer look on spots with marine pollution. They have also set up a device called a “KAKAXI” to measure how long it takes for marine litter and other pollution to accumulate after they clean up the coast. Most municipal governments don’t have a handle on just how much sea waste is washing up on their shores, so we’re hoping we can sell this information to them as a service.

With Amanogi as its leader, the team is made up of members from Nagasaki University, ACSL, Drone Create, Ridge-i, Know inc., University of the Ryukyu, and Drone Fund.

The second team is called “Decentralized Energy” and they are working on processing plastic harvested from the ocean.

Due to the salt absorbed by sea pollution, it can’t be burned with a regular disposal incinerator. What this team does is use subcritical water and high pressure to turn the salty plastic into fuel pellets. The pellets can be burned at thermal power stations to create energy. This means we can create energy from sea waste. Their goal for the first year was to develop a vehicular subcritical water processor to send to spots where there is lots of marine litter and turn the marine litter into fuel pellets.

They are also currently applying for a patent for a technology they developed to siphon out microplastics that can’t be processed at their plant in the first year. This technique is another step in creating a circular economy, where marine litter is recycled into energy.

With the Sustainable Energy Company as their leader, other team members include Novelgen, Retechflow, and Monju.

Our third team is called “Material Circulator”, with a mission to make profound products out of sea waste. It is working on a way to make collecting marine litter from the oceans an activity people can participate in.

The team leader, the Manatee Company, specializes in collecting sea waste in Okinawa. Tourists there use special bags to collect any waste they see on the shores, and bring those bags to designated restaurants. They use the plastic, especially those that come from fishing, to create a material that can be used to make things like bags to collect more marine litter. They also found that man-made grass that finds its way into rivers can make its way to the ocean and end up turning into microplastics. They recycle sea waste and man-made grass into a sheet of material that can be used to create things like amenity bottles for hotels. During their first year, they found a way to make the sheets out of plastic using university research. This system allows tourists visiting Okinawa to play a role in cleaning up the oceans.

JLE (currently Manatee) is team leader, with team members from TBM, Pirika, and the Tokyo University of Science.

The First Year's Results for the Satellite and Drone Monitoring Team

―Could you tell us a little more about the satellite and drone based sea waste detection system created by the Debris Watchers?

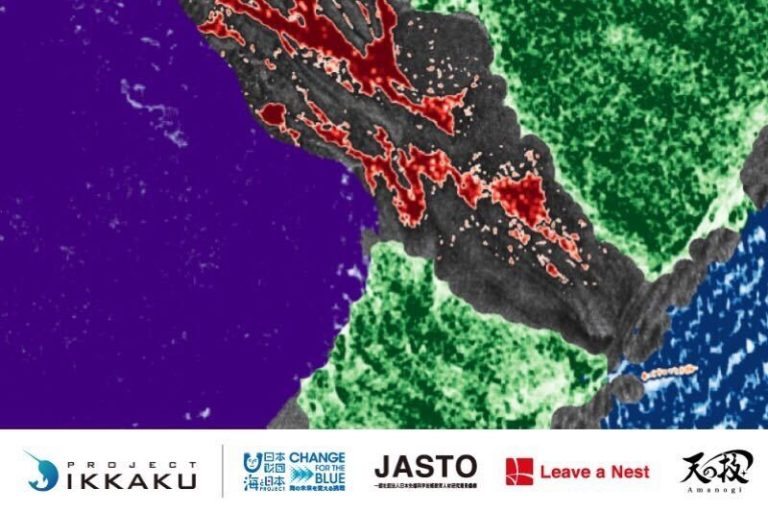

Ueno:Thanks to satellite technology, we use a combination of overseas optic images and SAR images to check whether or not there is sea debris building up around Taima City in Nagasaki, Masuda City in Shimane, and Okinawa. For example, by extracting the difference from before and after we clean the shore, we can tell whether or not there is any marine litter left after we finish cleaning. After developing this method, we had the chance to use it in August of 2020 when a merchant ship had an oil spill off the shore of Mauritius. We shared the results of our detection of the extent of the spill in a press release.

We used satellite images to get a general idea of where sea waste accumulates, then use drones to get a better picture. After getting more familiar with the data, we can now detect nine different types of sea pollution, including styrofoam, fishing nets, buoys, driftwood, and other types of wood, etc.

We also have found a use for a fixed point observation device usually used for agriculture called “Kakaxi”. It’s a device that analyzes image data, normally used to detect temperature and rainfall. By using this fixed point observation device, we’ve been able to deduce a process for recollecting marine litter after a collection has been done. There were things we were unable to account for, such as strong coastal winds, so we need to figure out a way to keep the device stable. This is something that will carry over into our second year.

We’re hoping that we can turn this project into something that receives a budget for keeping Japan’s oceans clean. Right now, that budget goes to municipal governments that are tasked with keeping tabs on how dirty their shorelines get and keeping them clean. We’re hoping we can sell our data to such entities. Being able to extend our coverage to all of Japan is one of our next big hurdles we need to overcome. We’re also thinking of making a “Combat Marine Pollution Communication Website” where we publicize the spots where lots of marine litter accumulates so that the teams that turn marine litter into resources can go to those spots and recycle waste.

Project IKKAKU in its Second Year

―What will the teams be doing for their second year, where they are tasked with turning their service into a business?

Ueno:We are currently observing the accumulation of sea waste at around ten spots. There are lots of places where we don’t observe marine pollution, or it has yet to become a problem, which results in there being a lot of areas around Japan that, quite frankly, aren’t conscious of putting the necessary resources into fighting the problem. We’re hoping that by making the information available using Debris Watchers, we can help push parts of Japan that have yet to face the problem to start playing their part as well. Another way we hope to push these regions is to create the impression that the more marine litter they have, the more money they stand to make by recycling it. If we can make that possible, I imagine more data would be used by more regions. This is the advantage of having the public sector involved with our movement.

One of the things we need to work on for our second year is the brand recognition for Project IKKAKU itself. We’re hoping to create an international team to go to summits abroad related to the ocean. We’d also like to team up with larger companies to be a part of their corporate social responsibility bids. Having larger partners could really speed up our efforts. The way we created Project Ikkaku could also be used to solve other social problems as well, so we hope to get the word out about how we operate.

By expanding the project’s scale, we’re also hoping we’ll receive more demands from the public sphere. Having concrete demands will help us understand where there are needs, something we need to have a strong understanding of moving forward. Depending on what those demands are, could even potentially restructure the whole project.

Editor's Notes

You’d be hard-pressed to find someone against cleaning the ocean. With the sheer volume of marine litter that enters the world’s seas every year, whether it be from fishing or plastic waste, it is impossible to solve the problem using only volunteers. There is really no way to approach problems that are so large in scale. Ms. Ueno spoke about how Leave a Nest’s method of creating hyper diverse teams, monetizing, and having the movement revolve around start-up companies may be the best way to move forward. Whilst satellite technology plays an integral role, being able to tell where the marine litter is, is only part of the equation. The final goal for this movement which utilizes a diverse set of scientific fields and technologies is to figure out how to clean up our oceans and promote it organically all around Japan.