[Special Interview with the Founder of TerraWatch Space] An Ideal Scenario for the Use of Earth Observation Data Across Industries and the Role of Government Support

We discussed a variety of topics, including how Earth observation satellite data can be more widely utilized and what the ideal form of government support for the commercialization of Earth observation services might look like.

Do you know the website TerraWatch Space?

A person who has supported SORABATAKE(※) since its early days asked me, “Have you seen this site?” That’s how I first learned about “TerraWatch Space,” and the SORABATAKE editorial team was genuinely amazed. It’s a site dedicated entirely to sharing information on the use of earth observation. Not only does it provide frequent updates—about once a week—on global trends, but it also publishes articles that feature infographics and in-depth insights.

※Sorabatake is a web-based media to accelerate space business in Japan (mainly focusing on EO satellite projects, but not limited to.) It was established by 2017 by a voluntary group. And from 2018, it is operated as the official media of Tellus (Japan’s EO satellite data portal) .

When I found out that TerraWatch Space would be hosting an event called “EO Summit” in New York in June 2025—an event dedicated to the commercial use of Earth observation satellite data—I became increasingly curious: what motivated the person running this initiative, and how did they get started?

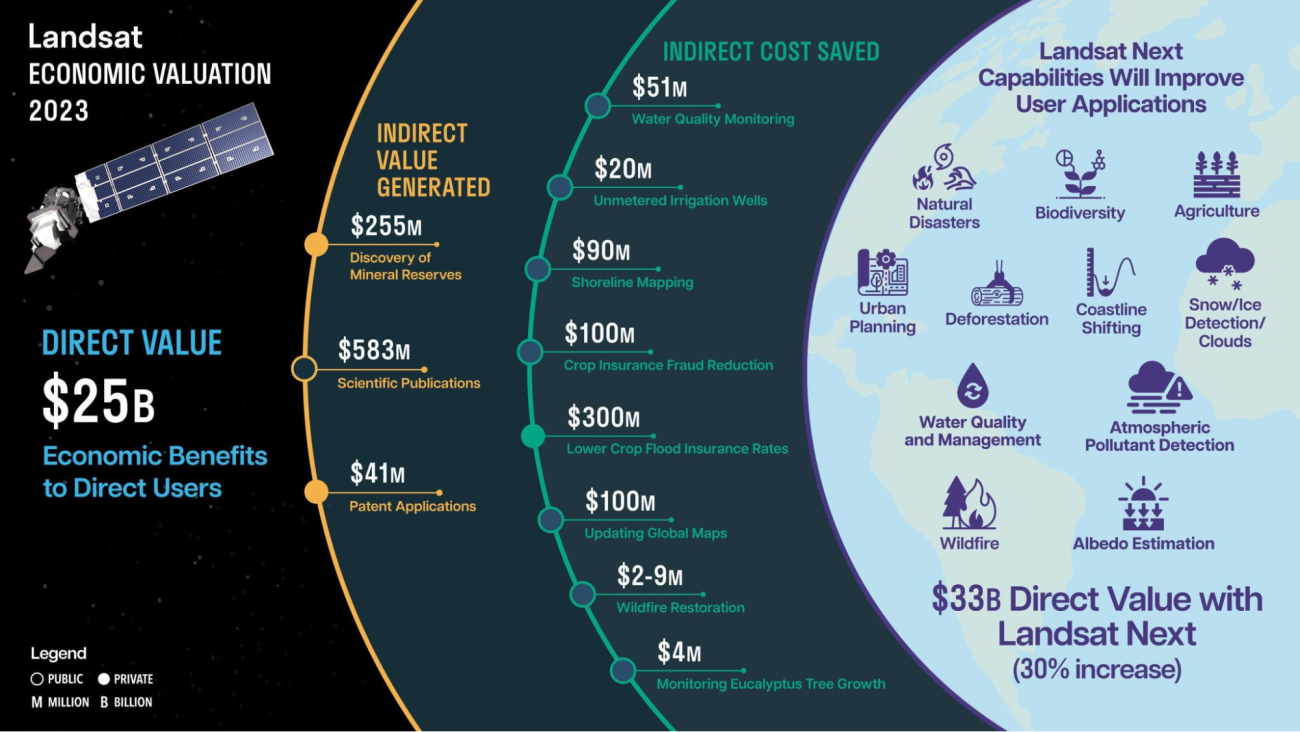

Recently, I was fortunate enough to have the chance to speak with Mr. Aravind Ravichandran, the founder of TerraWatch Space. Aravind currently advises businesses, space agencies, and investors. He also took part as a co-author in the “ECONOMIC VALUATION OF LANDSAT AND LANDSAT NEXT (2023)” report compiled by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and is actively engaged in efforts to further the utilization of Earth observation.

In our conversation, we covered a wide range of topics, such as how Earth observation satellite data—expected to see even broader use in the future—could be more widely leveraged, and what an ideal form of government support might look like for commercializing Earth observation services.

The Potential and Challenges of Earth Observation Data, Noticed During PwC Days

SORABATAKE: We have taken a look at TerraWatch Space and learned a lot about Earth observation. To begin, could you tell us how you got started with this initiative? What inspired you, and how did it all come about?

Aravind: I’m originally from India and started my career at Amazon in India, with a background in computer science. After that, I moved to Europe, where I earned my master’s degree in business administration.

It was in 2016 that I entered the space industry. I took on space-related consulting projects at PwC, and that was my first encounter with Earth Observation (EO) technology. From there, I was struck by how expansive its applications could be and realized its significant potential value. At the same time, I began wondering why EO wasn’t yet a mainstream part of business.

Later, during the COVID-19 period, that question kept lingering in my mind. In 2020, I left PwC and shifted my career focus entirely to Earth observation.

SORABATAKE: So this led to founding what is now “TerraWatch Space.” Could you elaborate on how you recognized the high potential of Earth observation?

Aravind: First and foremost, there are many applications. Not only does a massive volume of data already exist, but I also saw the promise of many more applications emerging across various industries in the future.

One example that really impressed me, illustrating the diversity of data that Earth observation satellites can capture, is environmental monitoring. From Earth-observation satellites, we can gather everything from soil moisture and atmospheric water vapor to wind speed data.

On top of that, once we know soil moisture levels, we can estimate crop yields in agriculture. From an infrastructure monitoring perspective, an increase in soil moisture could indicate a water leak in a pipeline. I was fascinated by how a wide range of data can be applied to a wide range of industries, thereby expanding its applications.

SORABATAKE: So there is a wide variety of data, and that data can be further developed into a variety of applications. On the other hand, you mentioned that there are challenges preventing EO from becoming more mainstream. What do you see as the main causes?

Aravind: I think there are primarily two challenges. The first is an “awareness gap,” meaning that many people aren’t sufficiently aware of satellites or how to utilize satellite data. The second is an “adoption gap,” where people may know about satellite data but don’t know how to practically integrate it into their workflows.

To tackle these issues, I work on consulting and information-sharing activities. That includes supporting end-user companies in sectors such as insurance, agriculture, and mining, as well as assisting with Earth observation strategies and intergovernmental collaborations. Through these efforts, I aim to expand awareness of Earth observation and encourage its adoption.

Toward a Future Where Tens of Thousands Understand Earth Observation and Hundreds of Millions Use EO-based Applications

SORABATAKE: Regarding the “awareness gap,” how many people do you think need to be familiar with Earth observation in order to expand its use even further?

Aravind: I don’t think all 100 out of 100 people need to know about Earth observation. Take weather forecasts, for instance—most people use them, but very few actually know how those forecasts are generated using Earth observation.

Most users just want convenient applications; they aren’t necessarily interested in how those applications (in this case, Earth observation) work behind the scenes. This doesn’t just apply to weather forecasting; it’s true for agriculture, insurance, mining, and other industries as well.

SORABATAKE: So which types of people, and roughly how many, need to be aware of Earth observation?

Aravind: In my view, it’s enough if tens of thousands of people who can actually develop applications understand what Earth observation is. The vast majority of people who simply use those applications don’t really need to know.

The Space Industry Is Inward-Focused and Needs to Reach Out

SORABATAKE: So the “awareness gap” boils down to the fact that potential developers of applications aren’t sufficiently aware?

Aravind: People who can develop applications are data scientists and those able to handle geospatial data. They might not be experts in Earth observation, but once they know what satellite data can offer, they have the capacity to build powerful applications.

We need to raise awareness and communicate what data can be derived from Earth observation and what that data makes possible. That’s the “awareness gap” I initially mentioned.

SORABATAKE: These are exactly the kinds of people we want to reach through SORABATAKE’s information outreach. I also believe it’s important to provide information to those working in various industries who use these applications. What do you think?

Aravind: I feel that the Earth observation industry—and the space sector as a whole—is still very inward-focused and needs to step outside its own sphere. By going outward and entering the markets where people actually use these applications, we can figure out what really needs to be developed.

For instance, those in the Earth observation industry might think it’s extremely helpful to look at images of Earth on a daily basis. But in the insurance industry, for example, they probably don’t need to examine every property every single day.

So, there are some cases where we are answering to their problem, but then there are many cases where we have technology, but we are not really answering to any of their problems.

The key is building applications that address real user needs, and to do that, you must have a solid relationship with those users.

An Ideal Scenario for Information Sharing That Advances Earth Observation Usage

SORABATAKE: SORABATAKE is currently a media platform visited by 80,000 to 100,000 people each month. Most of these visitors find us by searching terms like “satellite data,” “SAR,” or “space business.” In this day and age—often referred to as living in a “filter bubble” or “echo chamber”—people can easily encounter information they’re already interested in, but it’s hard for them to come across new information if they have no interest in it from the start.

From your perspective, what does an ideal information-sharing approach look like for facilitating greater use of Earth observation?

Aravind: At present, outside of independent media outlets specializing in space, companies like MAXAR or Planet Labs are disseminating information on Earth observation in other markets. However, that’s largely part of their marketing strategies, so it’s not a perfect form of communication that can fully close the awareness gap.

That’s why I hope TerraWatch Space will eventually be able to conduct outreach that truly helps develop diverse applications for a variety of industries.

From an information-sharing standpoint, my idea of the best-case scenario is that industry-specific media—like those dedicated to agriculture or insurance—will start featuring stories about how Earth observation can be utilized. As of now, there hasn’t really been a movement where specialized media in each industry actively covers Earth observation, but I believe EO is an incredible technology that will become impossible to ignore in the future.

I’m an expert in Earth observation, but not in every industry. It makes more sense for specialists in each field to explain how Earth observation can be applied effectively in that domain.

SORABATAKE: In Japan, for instance, it could mean outlets like the Japan Agricultural Newspaper or the National Agricultural Newspaper featuring articles on Earth observation-based applications.

Two Examples That Transformed Their Industries Through the Unique Strength of Earth Observation Data—Insurance and Power

SORABATAKE: Regarding the use of Earth observation data, do you have any thoughts on what an ideal process would look like from initial demonstrations to full-scale implementation in society? In many cases, pilot programs never progress into actual deployment, so if you have any ideas on how to increase real-world adoption, please let us know.

Aravind: That’s hard to say, because the situation can vary significantly depending on the market. In many markets, you need a lot of pilot programs and demonstrations to validate the real-world feasibility of satellite data. In some cases, drones or aerial imagery might actually be the better solution.

Moreover, satellites aren’t necessarily perfect for every domain. Just because you can use them doesn’t mean you always should.

On the flip side, a good example of where satellite data has sped rapidly through to real-world adoption is in insurance payouts following natural disasters.

When a flood occurs, you naturally want a map to understand the extent of the damage. In such cases, Earth observation from satellites is one of the best options. After a flood, it’s common to have heavy cloud cover or poor weather conditions, which can make it difficult to deploy aircraft. However, with SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar), you can still detect the extent of flood damage even through clouds. In applications like this—where the unique strengths of satellites can really shine—the validation and demonstration phases tend to be relatively straightforward and can move forward quickly.

In fact, many insurance companies are now incorporating satellite data into their claims payout processes, so they can assess damage without having to send people out for on-site inspections.

Related Articles on SORABATAKE

・Practical Deployment Is Almost Here! Early Flood Damage Assessments Using Satellite Data: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at a Loss Assessment Pilot”

・“QPS Institute and Tokio Marine & Nichido Collaborate on a Global Enterprise Risk Management Service Leveraging Satellite Data [Space Business News]”

SORABATAKE: Thank you. Just like the insurance example, are there any other cases where, in your experience promoting Earth observation, you think to yourself “It would be great if more examples like this continued to emerge”?

Aravind: Absolutely—there are quite a few.

One more example is the management of power transmission lines in the electric power industry. Power lines, which bring electricity to our homes, stretch across virtually every corner of the globe.

They reach very remote areas, and naturally, some get damaged. For instance, strong winds might cause nearby trees to topple onto the lines, causing them to break and interrupting the power supply.

This is where satellite data comes in. Using the data, you can figure out things like “This area has a lot of trees that could fall onto the lines in high wind” or “These trees around the power lines have a high risk of wildfire.” In other words, satellite data helps identify exactly where the risks are. Moreover, these days you practically can’t plan where to preemptively remove trees to protect power lines without satellite data.

The insurance and power-line management cases both illustrate how satellite data has transformed entire industries. Before, it was nearly impossible to comprehensively survey large areas without satellite data. Now, you can pinpoint where there’s a risk of falling trees or where damage has occurred, which helps you determine where to dispatch personnel. These examples show how satellite data is actively reshaping several industries.

The Ideal Form of Government Support in Promoting Earth Observation Data Usage

SORABATAKE: Thank you for sharing these excellent examples. Next, could you tell us what you think governments can do to help foster more of these kinds of success stories?

Aravind: One primary form of government support would be to make satellite data freely available to private companies, the way the United States has done with the Landsat program and Europe has done with the Copernicus program.

By freely releasing data collected by Landsat and Sentinel, a wide array of applications and innovations emerged. As a result, a new market began to take shape.

Aravind: I know Japan also has several satellites, but what’s even more crucial is making the data more user-friendly and more readily accessible, so that a larger number of people can actually work with it.

I believe the most vital point is ensuring that users can easily access and utilize this data. In other words, it’s important not only to invest in satellites themselves, but also to invest in concrete tools for data distribution, so that people can simply plug in and start leveraging the data.

SORABATAKE: Thank you. Even from Japan, we can really sense how freeing up Landsat and Sentinel data has sparked a variety of new markets. Is there anything else governments can do to support?

Aravind: Definitely. Beyond that, I think they can also run competitions or “challenges” aimed at solving specific issues. For instance, if there’s a certain problem in agriculture, a government ministry related to agriculture could launch a competition to tackle that.

In such a setup, the government would not only provide funds to the winning teams or companies but also become a direct customer of their solutions. That way, the approach can be sustainable long term. If an excellent solution emerges, that agricultural ministry would actually adopt it.

SORABATAKE: Thank you. So making Earth observation data freely available and having public agencies serve as customers to help build new markets—those are two important forms of government support.

Planet Is Expected to Turn a Profit in Fiscal 2025. How Deeply Should Governments Involve Themselves in Industry Growth?

SORABATAKE: One more question. Planet Labs— which operates the world’s largest commercial Earth observation satellite constellation— is projected to become profitable in fiscal year 2025. Do you think the government’s role will change in such a scenario?

Aravind: That’s an interesting question.

First, I want to mention that Planet has not yet turned a profit, but they’re hoping to become profitable sometime in FY 2025. Whether they succeed depends on what contracts they can secure and how much demand there is for their data.

So far, Planet’s growth seems to stem primarily from the defense sector. This is common to many Earth observation companies, and I suspect we’ll see the same pattern continue for the next few years. The defense industry has a substantial budget and a relatively strong grasp of what the technology can do.

SORABATAKE: Planet’s financial reports do mention strengthening contracts with key customers. So it’s the defense sector that’s the main driver, right?

That being the case, do you think the government should also actively support companies as they expand into markets beyond defense? Or do you feel that’s solely a matter of corporate initiative and not the government’s role?

Aravind: I don’t think the government’s role is to create an industry on behalf of companies. It’s up to the companies themselves to develop the market.

What the government can do is become a customer and provide support. The government can’t create the market itself. As you know, governments already do things like fund research, support technology development, and act as a customer.

So, at this point, it’s the companies’ responsibility to verify whether their technology truly works in specific industries. That’s essentially a question of the company’s own marketing and products—whether they’re offering the right solution.

And if it doesn’t go well, it’s also up to the company to change its products, technology, or strategy.

EO Summit in June 2025 Will Focus on Commercial Uses of Earth Observation Data, Excluding National Security

SORABATAKE: One final question. Regarding the EO Summit scheduled for June 2025, I see there are four designated industry tracks. Could you share the reasoning behind selecting those four tracks? What factors were most important, and did you consider overall market size?

Aravind: First and foremost, we wanted to feature a variety of industries and use cases. That was our main goal.

By showcasing different use cases, we want participants to learn about a range of sectors and applications.

TerraWatch Space’s market analysis usually covers both government and commercial markets, but there are already plenty of conferences focused on government and defense. This time, we decided not to include them, focusing instead on the commercial side.

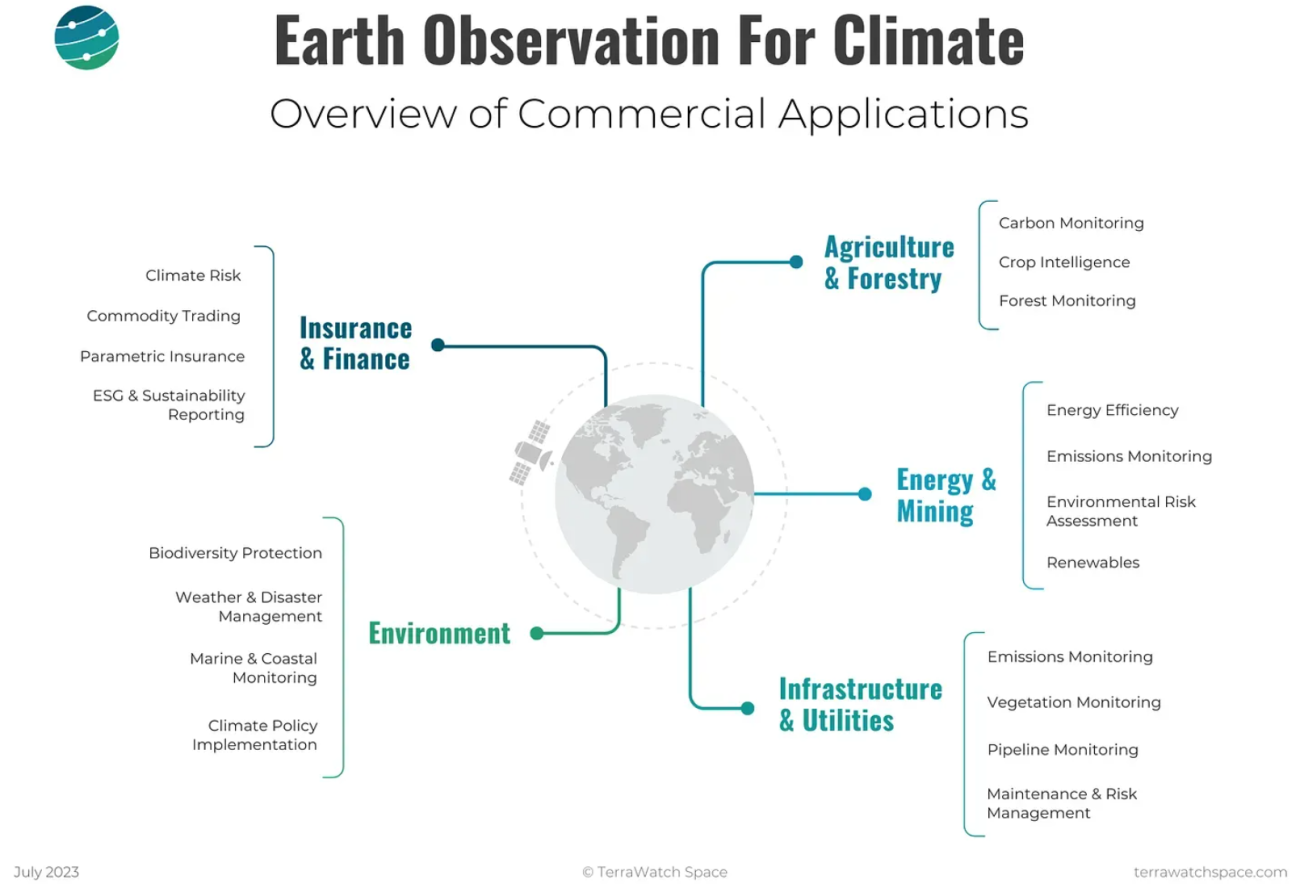

Our aim is to host an event that comprehensively surveys commercial Earth observation. That’s why we’re not incorporating defense or government aspects. Instead, we’ll be covering areas like insurance, finance, agriculture, forestry, energy, public utilities, the environment, and climate.

Of course, government bodies may be indirectly involved—like an agriculture ministry for farming, or an energy ministry for power generation—but our main goal this time is to showcase commercial use cases.

As for market size, you can make any sort of estimate, but it’s hard to pin down precisely. Hence, we place more emphasis on the diversity of applications and on ensuring a wide variety of participating companies, rather than focusing on market size alone.

SORABATAKE: Thank you. This interview has made me even more excited about attending the EO Summit. I’m really looking forward to meeting you in person this June!