JICA aids the Cambodian Countryside with Hydroelectric Power. How extensive is the electricity? Satellites beautifully show us the exact incredible extent!

JICA's Evaluation Department is using satellite data to evaluate the effectiveness of their foreign aid. What exactly is the Evaluation Department's idea for using satellites?

The “Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)” has approximately 90 locations around the world and conducts international cooperation with over 150 developing countries. JICA is also known for its previous president, Sadako Ogata, who was awarded the UNESCO peace prize.

JICA is currently working with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to tackle major problems around the globe, such as illegal deforestation and the illegal operation of sea vessels, by creating new services that utilize satellite data. (Click here for more details.)

These satellites are also being used by JICA’s Evaluation Department to measure the effectiveness of their foreign aid. What exactly is the Evaluation Department’s idea for using satellites?

JICA's mission! To send electricity to the Cambodian countryside.

The Japan International Cooperation Agency (referred to below as “JICA”) stands at the forefront of Japan’s foreign aid activities. As the organization that provides the Japanese government’s official development assistance (ODA), JICA provides many facets of aid, including public health, infrastructure (water, electricity, transportation, and other economic fundamentals for society), education, agriculture, industrial technology, computer technology, and more.

The province of Ratanakiri in the northeastern part of Cambodia is one of the areas that currently receives aid from JICA. This area, famous for its cashew nuts and coffee, is home to over 200,000 residents, many of whom are part of tribes that dwell in the mountains.

Cambodians living in this area are accustomed to buying electricity from the neighboring country of Vietnam, but with volatile prices, it can get expensive. It was common for electronic appliances, not to mention computers and the internet, to be rendered useless due to the insufficient power supply All the people of Ratanakiri prayed for, was the ability to make their own electricity.

JICA decided to answer these prayers, and started a project in 2013 to create electricity using lake water from within the province. They started the construction of a small hydropower plant that drops water to create electricity.

With power lines now extending throughout the province, the long-anticipated second power plant started operations in 2015. This brought an end to this JICA project in Cambodia.

Were they able to get the electricity? The "Evaluation Department" Sees Hope

An important part of JICA’s projects is the phase where they measure the effectiveness of their projects.

– Did the project meet the needs of the people it serves?

– Was the goal set at the beginning met?

– What changed for the people living in the region?

– Were resources invested efficiently?

– Have the effects of the aid lasted since the project finished?

These are the benchmarks used to closely evaluate the results of a project, with each benchmark eventually receiving a grade from A~D. Data from both effective and ineffective projects are compiled to be used when planning future projects.

Juri Ishimoto was the JICA Evaluation Department member who was in charge of giving the post-project evaluation on the small hydropower plant project in Ratanakiri, Cambodia.

Mrs. Ishimoto: The important question we must ask when evaluating the project conducted in Ratanakiri is, “Were we able to bring electricity to more people than before?” “Has the economy improved thanks to the newly available electricity?” This is what JICA is concerned with. To do this, they gather data in the country they intend on aiding beforehand, and then again after the project has finished. They compare these two sets of data to give their final evaluation.

For larger projects such as this, JICA will usually hire a consultant who specializes in evaluations. Mrs. Ishimoto had a third-party begin their survey, which brought a problem to light.

A Sudden Accident! This could make it hard to detect this project's effectiveness.

Normally, “gross regional product (GRP)” is the benchmark used to judge the growth of the economy by region. JICA made an effort to get data on the region’s GRP, but..

Mrs. Ishimoto: After surveying the region, we realized that there was no data up until that point. There was no public data on the GRP for Ratanakiri. Our consultant suggested using the changes in public facilities (i.e. schools, hospitals, etc.), but we weren’t sure any of these would really be true indicators on the economy.

Mrs. Ishimoto, at a loss for how to proceed with this project, had a lucky breakthrough during a Google Earth Engine seminar she just so happened to attend.

"This is it!" Night light could be an indicator of economic growth.

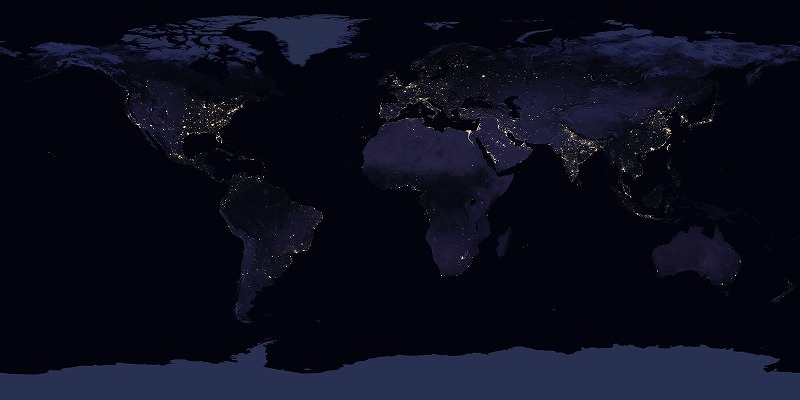

Mrs. Ishimoto: I heard at the Google Earth Engine seminar that data on night light has a strong correlation with economic growth. I thought, “This is it!” and immediately brought it back to my boss, and made the decision to use satellite data.

Sorabatake Memo

What is Night Light?

Let’s look at examples of night light below. (Click here as well for more details!) There are satellites that can take pictures of lights on the earth during the night.

This marked the start of Mrs. Ishimoto’s mission to learn everything she could about night light! Mrs. Ishimoto originally studied ways to make evaluations using numerical data, a study called “impact evaluation”, at graduate school. This would be her first time using satellite data.

The person who taught Mrs. Ishimoto what she needed to know about how to use satellite data was Masamitsu Kurata, a professor at Sophia University that helps JICA’s Evaluation Department together with Metrics Work Consultants.

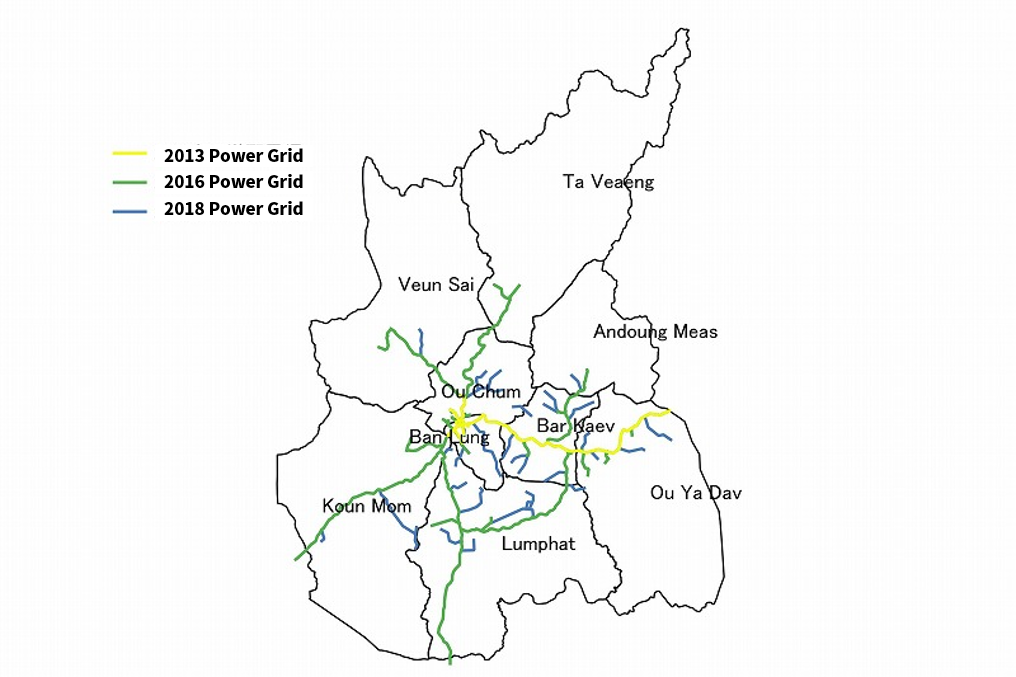

Mrs. Ishimoto: In addition to teaching me about night light data, Professor Kurata coached me on how to make map data on Ratanakiri using open data. They created a shapefile showing a network of power lines stemming from the power plant to form a power grid, and made a map to cross-reference the data.

Sorabatake Memo

What is a Shapefile?

This is a file that has data on shapes and attributes (properties, characteristics, numbers, etc.) assigned to those shapes.

Mrs. Ishimoto: I never would have imagined how difficult it would be to make a shapefile on my own. It took me at least seven weeks just to cover this small area. I learned Google Earth this past year (laughs).

The project was a huge success! A whopping 80% of people were able to receive electricity.

“Were we able to bring electricity to more people than before?” “Has the economy improved thanks to the newly available electricity?” The question is, “Just how effective was this project?”

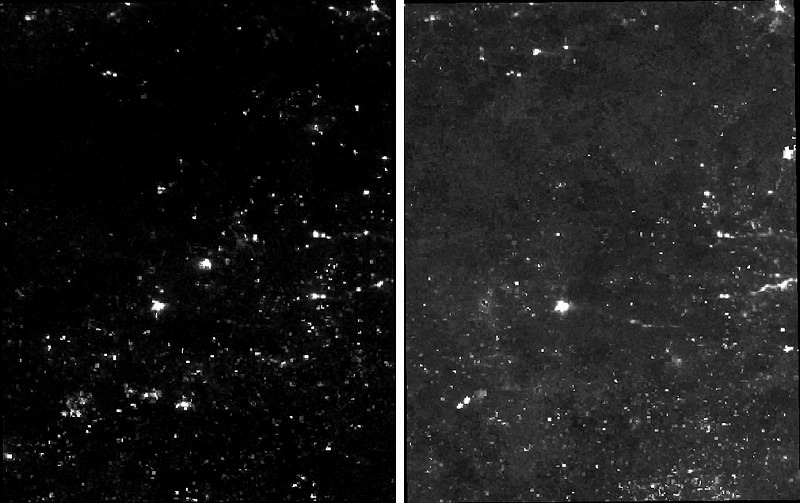

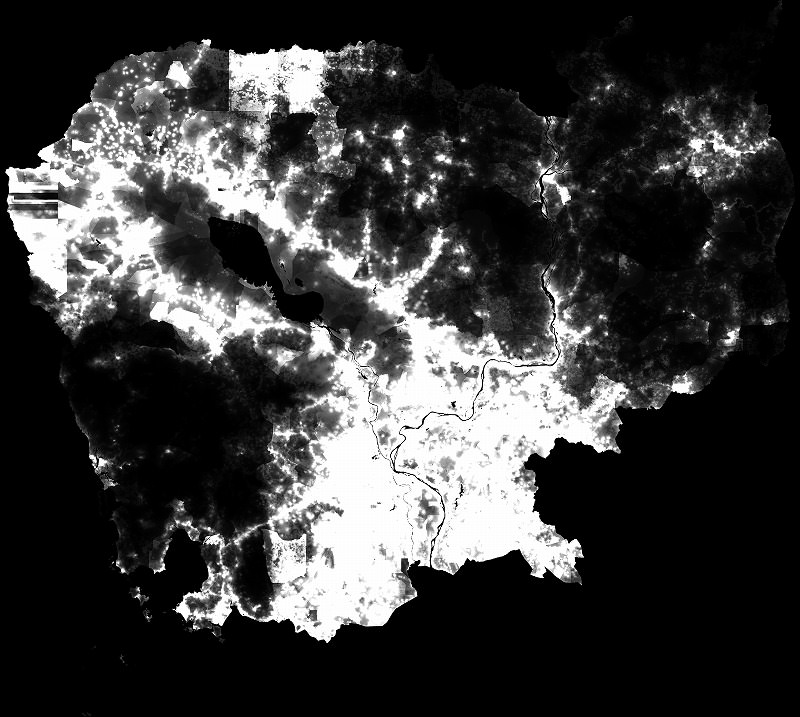

Mrs. Ishimoto: The first thing we looked at was a simple comparison of the night light data. While it is hard to see any electricity due to the mountainous nature of the area, when you compare the before and after images, you can see that there is now electricity there.

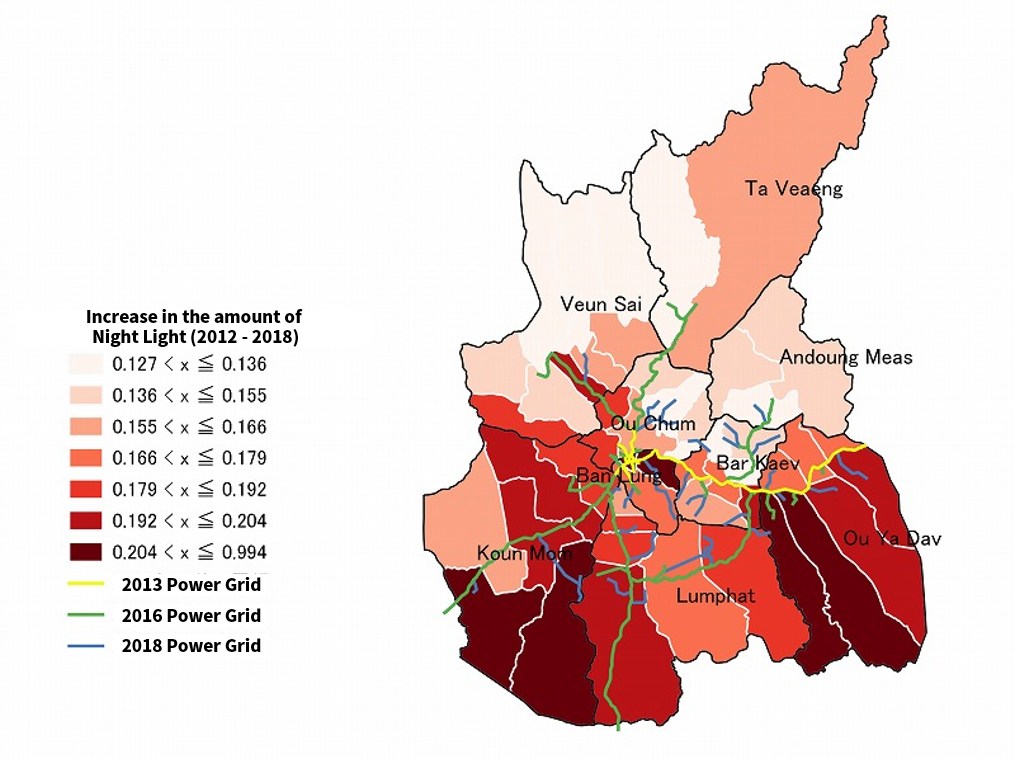

Mrs. Ishimoto: Next, we cross referenced this with a map that shows an increase in night light. Areas with a darker red show a higher increase in night light.

Mrs. Ishimoto: This shows us that the impact of this project extends far beyond the area around the power plants to the entire province. I must admit, the moment I saw these results I was really moved!

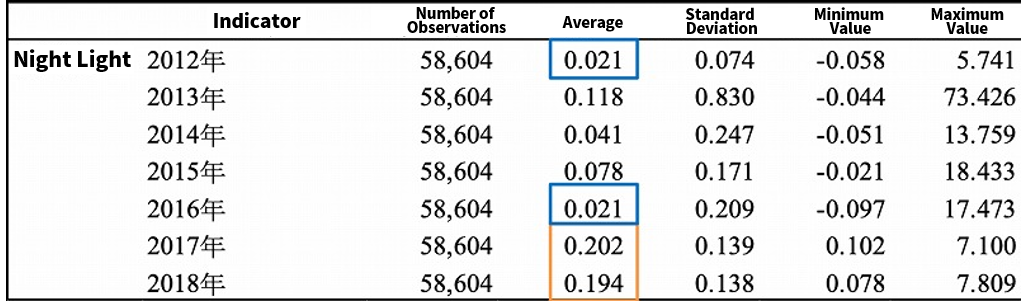

Mrs. Ishimoto: Electricity first started being used in 2015, after the power plant was finished. That year was met with an El Niño phenomenon which decreased the amount of rainfall in the region, resulting in the amount of water in the reservoir to temporarily decrease. This had a negative impact on the amount of electricity produced, causing there to be less light in the area, but in 2017 when water levels returned to normal, the energy levels increased, leading to a sudden increase in brightness. We believe this is the positive effect the fully functional power plant has had on the area.

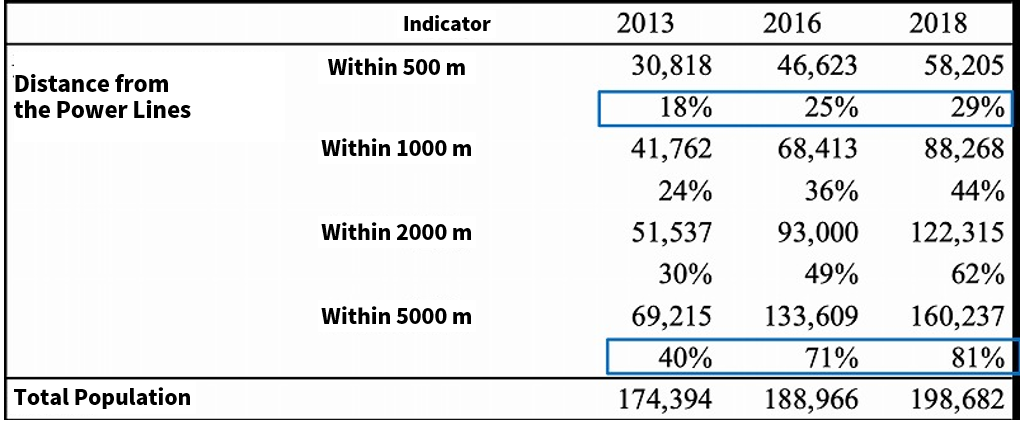

Mrs. Ishimoto also used population data from “Worldpop” provided for free by the U.N. as another data point to show the effectiveness of this project. By calculating the number of people who live close to the power lines, it is possible to get a concrete number on how many people are receiving electricity.

Mrs. Ishimoto: These are the results we saw after adding data from Worldpop.

Mrs. Ishimoto: When looking at the population within 5000 meters of the power lines, what used to be 40% of the province’s population jumped to 81%. This is an estimation based on numbers. It may be more accurate to say that electricity didn’t find its way to 81% of the population, but this part of the population now has a chance to access electricity. Any which way, if four out of five people can now possibly access electricity, I would call that a huge step forward for the region.

Through doing this, JICA was able to use satellite data to prove the impact their project had on the society and economy of Ratanakiri. This project received an A grade, the highest grade possible. The power plants have been well-maintained, and continue to produce electricity today.

Mrs. Ishimoto: If everyone in Ratanakiri can use electricity, not only will their standard of living increase, but it should have a huge impact on creating economic and industrial opportunities.

4 Advantages of Using Satellite data According to Mrs. Ishimoto of the Evaluation Department

1. You can clearly visualize the data!

Mrs. Ishimoto: For this project, I had to gather a lot of the data on my own, so I have a newfound appreciation for visualizing data. Being able to clearly show the results in a way that may be difficult to understand with just words and numbers is definitely an advantage you get with satellite data.

2. You can view more dangerous areas from a safe distance!

Mrs. Ishimoto: There are a lot of regions in the Middle East where JICA can’t actually go and collect data due to dangers in local security. Satellite data allows us to gather information in cases like these.

3. Use Free Data to Cut Costs!

Mrs. Ishimoto: We normally have to go to the region to collect the data we need. We have to actually survey the area, and speak with the locals to gather important data, which can cost a lot of money. Moving forward, the ability to use free satellite data to supplement our data will allow us to cut costs without sacrificing the quality of our data. I believe this will increase the quality of our projects as well.

4. A Wide Area can be Seen!

Mrs. Ishimoto: Some of our projects involve creating between 50-100 irrigation facilities over a wide span of land. When it comes time to evaluate said projects, we don’t have the time or money to evaluate all of the facilities. When this happens, we pick random facilities to survey, but in the future, if we are able to use satellite data, we will be able to check all of the facilities at a glance. This should have a huge impact on the quality of our research.

The JICA Evaluation Department's Dream to Use Satellite Data

JICA performs aid around the world in the fields of agriculture, public health, and much more. Mrs. Ishimoto, who covers mostly agriculture, is placing high hopes on the utilization of satellite data.

Mrs. Ishimoto: One of the major indicators of effectiveness in agricultural projects is measuring the increase in “irrigation area,” “cultivation area,” and “planting area”. Data on this can easily be collected by a satellite, and is definitely something I would like to use. I am also looking forward to the potential for satellites to collect data on harvests, which is still considered hard to gather data on.

Mrs. Ishimoto: While using satellites could be a dream solution, they also provide a challenge. The most difficult part is that we need specialists who excel at analyzing satellite data. I would love to partner up with a satellite data analyst to receive advice on how to make further use of satellites!

Post Script

JICA effectively used free data to ascertain night light, population, and map data. Not limited to foreign aid, the PDCA cycle is a necessary part of evaluating any project. For outdoor projects in particular, I feel like there are a lot of applications for satellites, especially with the C (check) part I would definitely like to learn more about how I can use them!